NYACP Board Review Question of the Week

Every other Tuesday, NYACP members are sent a Board Review Question from ACP's MKSAP 18 to test professional knowledge and help prepare for the exam. Participant totals and answer percentages are distributed on the first Thursday of the month in IM Connected, the Chapter's eNewsletter, and are also published on this page.

If you are interested in receiving these questions bi-weekly, join us as a member!

If you are a member who needs to receive the questions and newsletter via email, let us know!

February 10th, 2026

MKSAP 19 Endocrinology & Metabolism, Question 2

A 46-year-old woman is evaluated for type 2 diabetes mellitus. At the time of her diagnosis 1 year ago, metformin was initiated. Since then, she has been diagnosed with hypertension and dyslipidemia. Medications are metformin, lisinopril, and atorvastatin.

On physical examination, vital signs are within normal limits. BMI is 32. The remainder of the examination is unremarkable.

Today, her hemoglobin A1c measurement is 8.0%.

Which of the following is the appropriate treatment to start next?

A. Dulaglutide

B. Glipizide

C. Insulin

D. Pioglitazone

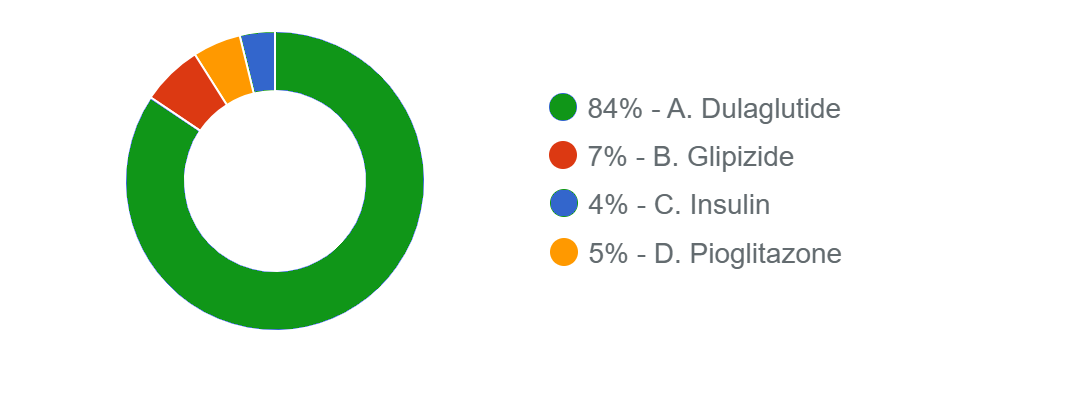

Responses Received from Members (712 Responses):

The Correct Answer is: A. Dulaglutide

Educational Objective: Treat type 2 diabetes mellitus in a patient with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk factors.

The best treatment option for this patient is to add dulaglutide (Option A). At the time of diagnosis, metformin was initiated, which is a first-line pharmacologic therapy for the glucose-centric management of type 2 diabetes mellitus. However, her glycemic target is still not at goal. In young, otherwise healthy patients, the American Diabetes Association recommends a hemoglobin A1c target of less than 7% in most nonpregnant adults. Patients should be re-evaluated at 3-month intervals and treatment escalated with additional agents if the hemoglobin A1c remains above goal. In patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and established atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) or multiple risk factors for ASCVD, a glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonist (GLP-1 RA) or sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitor with demonstrated cardiovascular benefit is recommended to reduce the risk for major adverse cardiovascular events, independent of hemoglobin A1c lowering.

This patient has multiple risk factors for ASCVD (hypertension, dyslipidemia, obesity). In addition, GLP-1 RAs are associated with weight loss, which would be beneficial for this patient with obesity. Dulaglutide is a GLP-1 RA with proven cardiovascular benefit.

Glipizide (Option B) is a sulfonylurea and stimulates insulin secretion. It is associated with weight gain and has no ASCVD benefits.

In most patients who need the greater glucose-lowering effect of an injectable medication, GLP-1 RAs are preferred to insulin (Option C). Insulin administration is not associated with the ASCVD benefits of a GLP-1 RA and may also cause weight gain.

Pioglitazone (Option D), a thiazolidinedione, increases peripheral uptake of glucose. Although pioglitazone can possibly decrease cardiovascular disease events, it is associated with weight gain, which is undesirable in this patient with obesity.

Key Point

- In young, otherwise healthy patients, the American Diabetes Association recommends a hemoglobin A1c target of less than 7% in most nonpregnant adults.

- A glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonist or sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor with demonstrated cardiovascular benefit is recommended in patients with type 2 diabetes and established atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) or multiple risk factors for ASCVD to reduce the risk for major adverse cardiovascular events.

Bibliography

ElSayed NA, Aleppo G, Aroda VR, et al. 10. Cardiovascular disease and risk management: standards of care in diabetes—2023. Diabetes Care. 2023;46:S158-S190. PMID: 36507632 doi:10.2337/dc23-S010

Multiple-choice questions reprinted with permission from the American College of Physicians.

MKSAP 19. © Copyright 2025 American College of Physicians.

All Rights Reserved.

January 27th, 2026

MKSAP 19 Cardiovascular Medicine, Question 11

A 70-year-old man is evaluated for recently diagnosed paroxysmal atrial fibrillation that is mildly symptomatic. Medical history is significant for hypertension and previous stroke. Medications are rivaroxaban and metoprolol. He has experienced no episodes of bleeding on anticoagulation therapy. On physical examination, blood pressure is 128/74 mm Hg and pulse rate is 72/min and regular. The remainder of the examination is unremarkable.

An echocardiogram reveals an enlarged left atrium and normal left ventricle. Forty-eight–hour ambulatory ECG monitoring shows atrial fibrillation prevalence of 10% with a controlled ventricular rate less than 90/min and no other abnormalities.

Which of the following is the most appropriate treatment?

- Left atrial appendage occlusion

- Pacemaker implantation

- Rhythm control

- Switch rivaroxaban to warfarin

- No additional therapy

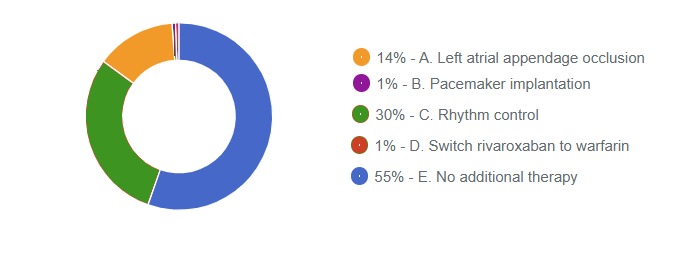

Responses Received from Members (661 Responses):

The Correct Answer is: C. Rhythm control

Educational Objective: Manage atrial fibrillation with early rhythm control.

Rhythm control (Option C) is the most appropriate treatment for this patient who presents with paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. This patient is reflective of those included in the EAST-AFNET 4 randomized clinical trial, which evaluated a rhythm control strategy versus usual care (typically including rate control) in patients with a recent diagnosis (within 12 months) of atrial fibrillation and coexisting cardiovascular conditions. The inclusion criteria were age older than 75 years or previous transient ischemic attack or stroke, or two of the following: age older than 65 years, female sex, heart failure, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, severe coronary artery disease, chronic kidney disease, and left ventricular hypertrophy. The trial demonstrated improved clinical outcomes, including a reduction in the primary composite end point of cardiovascular death, stroke, or hospitalization for heart failure or acute coronary syndrome, among patients randomly assigned to an early rhythm control strategy, including asymptomatic patients. The intervention included either antiarrhythmic drugs or catheter ablation, but importantly, it included aggressive concomitant medical therapy (e.g., oral anticoagulation when indicated, hypertension treatment) in both the intervention and the control groups. Based on the trial results, this patient is mostly likely to benefit from early rhythm control for atrial fibrillation.

This patient is appropriately receiving stroke prevention therapy with a direct oral anticoagulant (DOAC), and he has had no recurrent stroke or significant bleeding episodes on the current therapy. Therefore, left atrial appendage occlusion (Option A) is not indicated.

Among the common indications for permanent pacemaker implantation (Option B) are symptomatic bradycardia without reversible cause; permanent atrial fibrillation with symptomatic bradycardia; alternating bundle branch block; and complete heart block, high-degree atrioventricular (AV) block, or Mobitz type 2 second-degree AV block, irrespective of symptoms. This patient has no indications for pacemaker implantation.

Oral anticoagulation in patients with atrial fibrillation can be accomplished with a vitamin K antagonist (warfarin) or DOAC, such as rivaroxaban. Rivaroxaban is noninferior to warfarin in the prevention of stroke or systemic embolism and is associated with less intracranial and fatal bleeding. The 2019 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association atrial fibrillation guideline recommends DOACs in preference to warfarin in DOAC-eligible patients. Thus, there is no suggestion that switching to warfarin (Option D) would improve outcomes in this patient.

Offering no additional therapy (Option E) would be inappropriate because early rhythm control is associated with improved clinical outcomes in patients such as this one.

Key Point

- In patients with recently diagnosed atrial fibrillation and concomitant cardiovascular conditions, early rhythm control (antiarrhythmic drugs or ablation) reduces the primary composite end point of cardiovascular death, stroke, or hospitalization for heart failure or acute coronary syndrome compared with usual care.

Bibliography

Kirchhof P, Camm AJ, Goette A, et al; EAST-AFNET 4 Trial Investigators. Early rhythm-control therapy in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:1305-1316. PMID:

32865375 doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2019422

Multiple-choice questions reprinted with permission from the American College of Physicians.

MKSAP 19. © Copyright 2025 American College of Physicians.

All Rights Reserved.